Palatine Research

- The Palatine Families of New York, Jones, Henry Z.

- The Palatines Arrive in the Hudson River Valley 1710

- Genealogy Pages

The Palatine Families of New York, Jones, Henry Z.

A Study of the Geman Immigrants who arrived in Colonial New York in 1710; Universal City, CA, 1985

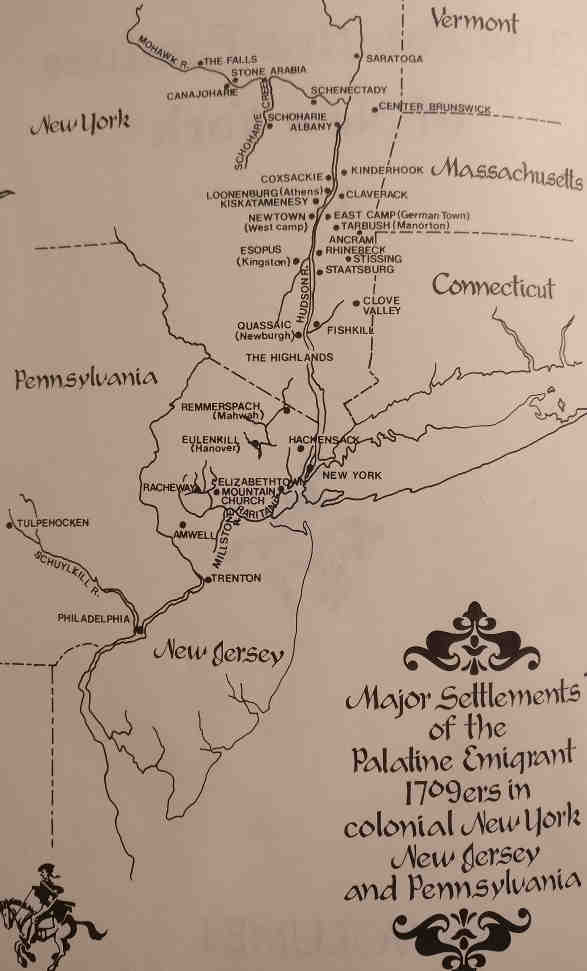

Map of Palatine Settlements

The Palatines’ Story

This work is © Jones, Henry Z., permission to reproduce pending

The background of the great "Palatine" emigration of 1709 has been

well-chronicled by such past scholars as Julius Goebel,. Sr., Friedrich Kapp,

Sanford H. Cobb, F. R. Diffenderffer, and Specially Dr. Walter A. Knittle. By

mainly utilizing state papers and official government records found in major

repositories and libraries in Europe and America, these noted historians did

fine work and broke new ground to give us "the big picture" of this great

exodus of Germans to the new world.

My own fifteen year Palatine project, howeyer, has approached this same

subject-matter from more of a genealogical rather than an historical point of

view (although, of course, both go hand in hand). I have studied the emigrants

themselves as much as the emigration, and thus have developed strong feelings

for the people involved as well as the events. The more I discover about the

Palatines from this personal perspective, the more my admiration and respect

for these courageous Germans grow, as I see how, after generations of

oppression and hardship, in 1709 they finally reached the limit of their

endurance and "took the risk" to find a better life in America.

Excellent historical background material on the Palatines, largely unexplored

by previous researchers, has been found in the 17th and 18th century

churchbooks of the towns and villages where the emigrants resided. These old

registers are treasure-troves of data on the local level, for ever so often

the Pastors, after recording a baptism, marriage, or burial entry in their

church-books, would comment on important matters of the day affecting their

congregations. Their notations often were written with such poignancy that

they capture the spirit of the times and the flavor of life in the local

Palatine community better than any other sources I have seen. For example, the

churchbooks often reflect the devastation and havoc caused by the repetitive

wars fought, on German territory - a major factor leading to the 1709

emigration. The Pastor at Partenheim near Aizey wrote:

1635 after March: Shortly after this time, we were ruined and destroyed

throughout the land by the Swedish and Emperor's armies, so that we

could not come back again until the year 1637.

Some years later, the Pastor at Westhofen noted;

1665: In the month of October, the by the Mainz-Lothringian invasion,

and the following children were baptised outside the area...

From October 1665 to 1669, this churchbook, along with my other best

books, were taken to Worms for security...

The plundering continued, as recorded by the as reported by the Pastor at Kröffelbach:

On Friday 21 Dec 1688, a large French force came here to Cröffelbach,

plundered everything here and at Oberquembach, Oberwetz, Niederwetz,

Reichskirchen [Reiskirchen] and other villages in the Wetterau,

demanded a contribution, and left again for Cassel by Maintz [Castel near

Mainz] and there crossed over the Rhine. I took flight and, through God's

help, escaped their hands.

One year later, the Pastor at Ginsheim echoed his colleague:

Because-of the soldiers remaining se long in our land, with the French

occupying the city of Mainz For two yrs., the German people have right to

complain stout the [troop] movements back and forth in these parts: the

Saxon and Bavarian armies are encamped in Niederfeld with 24,000 horse

and foot [soldiers], the Hessians are on the other side of Mainz, and the

Emperor's and [the] Lothringian troops are on the other side of tte Rhine

below the city.

The churchbooks themselves sometimes did not survive, as noted by the Pastor at Sprantal

Because in 1693 with the french invasion of Wirtemberg every churchbock - as

well as baptism and marriage record - met with misfortune, this new one has

been set up by me, the duly called Pastor here, ant in it at the beginning is

shown in orderly fashion all citizen/inhabitants with their families and the

surviving wives and ch., at the time of their baptisms, marriages, and burials

as later consecrated by me, so that each [subsequent] Pastor at the death of

any one of these [inhabitants] can easily set out and record their life history

without further research.

It is obvious from these contemporary, local accounts that 1709ers' families

had been living for generations in an area fraught with near-constant wars,

which made battlefields of villages, towns, and whole regions.

Besides being at the mercy of invading armies, many of these unfortunate

Germans were taxed unmercifully by whatever local Prince had jurisdiction over

their particular geographic region, and by 1709, many poor Palatines were bled

dry financiallY by their Lords. This was another reason for the exodus, as

evidenced by a portion of a letter written back to Germany in 1749 by

Johann Müller, an emigrant who finally settled in the Mohawk Valley of

Colonial new York:

Is it still as rough [in Germany] as when we left [in 1709]? As far as we

are concerned [in America], we are, Compared to taxes In Germany, a free

country! We pay taxers once a year. These taxes are so minimal that some

spend more money for drinks in one evening When going to the pub. What the

farmer farms is his own, there are no tithes, no tariffs, hunting and fishing

are free, and our soil is fertile and everything grows...

But perhaps the straw that broke the camel's back was the devastating and

bitterly cold winter of the year 1709. Throughout southern Germany, Pastors

abrubtly stopped their normal recording of baptismal, marriage, and burial

entries in order to mention the terrible weather conditions burdening their

congregations. The Pastor at Berstadt wrote:

[in the year 1709] there has been a horrible, terrible cold, the like of

which is not remembered by the oldest [parishoners] who are upwards of 80

years old. As one reads in the newspapers, it spreads not only through

the entire country, but also through France, Italy, Spain, England,

Holland, Saxony, and Denmark, where many people and cattle have frozen to

death. The mills in almost all villages around here also are frozen in,

so that people must suffer from hunger. Most of the fruit trees are

frozen too, as well as most of the grain...

The Pastor at Runkel noted:

[1709] Right after the New Year, such a cold wave came that the oldest

people here could not remember a worse one. Almost all mills have been

brought to a standstill, and the lack of bread was great everywhere. Many

cattle and humans, yes - even the birds and the wild animals in the woodsi

froze. The Lahn [River] froze over three times, one after the other...

At Diedenbergen another entry:

[27 Oct 1708] Before Simon Juda [Day], an usually heavy snow fell which

broke many branches off the trees, especially in the forests because the

leaves were still on the trees, and the snow weighed heavily on them. Then

on the day after New Year's, 2 Jan 1709 and for three days [thereafterJ, we

had continuous rain and later snow. Because of the great cold, the Main

froze over in four days, the Rhine in eight days, and they remained frozen

for five weeks. During this time there was a great lack of wood and flour,

since most miliS were frozen in. The fodder for cattle was used for two

purposes [the humans had to eat it too], and many a piece [of land?] was

ruined. One could read in the newspapers of many complaints and much damage

in all European countries.

And at Bolters even more:

From the 6th to the 26th of January [1709] there was such a raging cold, the

likes of which has not occurred in 118 yrs. according to the calculations

of the mathematicians at Leipzig. A great many trees have frozen, the

autumn sowing has suffered great damage, and this yr. there will be no

wine at all.

Residents of the various Duchies of southern Germany then were in a terrible

state from the ongoing wars, oppressive taxation, and devastating winter - all

of which contributed to their

desire to emigrate from their "forsaken Egypt," as Johann Müller of the Mohawk

called his former European homeland in his 1749 letter.

Interestingly enough, religious persecution does not seem to have been a major

factor in the exodus. Many of the Palatines seemed quite flexible in their

religious affiliatton; they attended whichever church was geographically

convenient or even politically expedient. For example, the 1709er

Johannes[\[1\]](NEEDLINK) Heiner was baptised a Catholic, married in the Reformed

church, then became a prominent Lutheran lay leader in the Hudson Valley.

Also, many emigrants who were noted in Germany and shortly after their arrival

in America as Catholics ("Episcopal" is Kocherthal's term for Catholic) soon

turned up as full-fledged Protestants in Lutheran and Reformed churchbooks of

colonial New York. It is intereeting to note that Neuwied and

Isenburg two of the prime German regions of origin for New York settlers,

both had atmospheres of religious toleration in the late 1500's - perhaps a

contributing factor to the later, theologically flexible viewpoint of many of

the 1709ers.

The British government exploited the Palatines' dissatisfaction by waging an

advanced and clever public relations campaign extolling the virtues of life in

the new world which also fueled the fires of emigration. This was accomplished

by the circulation throughout southern Germany prior to 1709 of the so-called

"Golden Book," which painted America (called "The Island Of Carolina" or "The

Island Of Pennsylvania") almost as the promised land of milk and honey. Its

effect is revealed by a marvelous series Of manuscripts entitled "Questions and

Answers Of Emigrants Who Intend To Go To The New Island, Actum 23 May 1709,"

found in the Staatsarchives Wiesbaden (Nassau-Weilburg File Abt. 150, No. 4493);

these documents are a boon for the genealogist, as they give the name, age,

religion, place of birth, length of marriage, and number of children among their

statistics for each prospective emigrant. They also enhance our view of the

daily lives of the Palatines, as each man is asked several personal questions

relating to his reason for leaving as well as how he will finance his journey.

The heart-rending responses to the queries are set forth in such a

straight-forward, conversational way by the Palatines that they almost seem to

make the emigrants come alive again. It is hard not to feel their despair and

not be moved by their cautious hope for a better lire in a new country. When

asked how he first came upon the idea to emigrate and who first gave a reason

for the emigration, Christian Schneider aged 25, Lutheran, married 2 years with

no children stated:

People from Altenkirchen. English agents at Frankfurt and writings brought

by them.

Johannes Willig aged 32, Lutheran, born In this country (Nassau-Weilburg),

married 8 years with 1 daughter, replied:

Because he's poor and has nothing more than he can earn by hard labour, he

seeks something better. At Grossen Linden he had a book about the Island.

When he was asked the same question, Johannes Linck aged 10, Lutheran, born Cöpern

in Hamburg an der Höhe, married 6 years with 1 son and 1 daughter, answered:

He cultivated in the winter and the grain was bad. He knows he can no longer

feed himself. He had heard of books about the Island and resolved to go there.

First heard of this froth people from Darmstadt who are going.

Hanß Georg Gäberling aged 40, Lutheran, came here from Lindheim an der Straße,

married 16 years with 3 daughters, responded:

Poverty drives him to it, in spite of working day and night at his handwork.

OtherWise he has no special desire to emigrate. He heard of books in Braunfels

and at Altenkirchen which Schoolmaster Petri at Reiskirchen brought to the

village on his deer-hunting.

Georg Philip Mück aged 32, Lutheran, born in this country, married 8 years with

1 son and 2 daughters, similarly replied:

Poverty brought him to it. He can hope for no harvest which the wild animals

have eaten. There have been people from the Pfalz in the village, and he

heard about it from them first.

Johannes Flach aged 30, Catholic, came to Nassau-Wellburg, married 10 years

with 3 sons, noted:

Poverty and no espeetation of [ever obtaining] land. Wild animals have eaten

everything. Has heard most about it at Frankfurt. He and G. Stahl bought a

book for 3 Batzen in which there is writing about the Island.

When asked another question, whether he received advice about this and from whom,

Philip Adam-Hartmann aged 31, Lutheran, born in this country, married 8 years

with 1 daughter, responded:

No [advice]. Only from God, because people so advise it.

And to this same query, Phil1ps Petri aged 42, Lutheran, born in this cOUntry,

married 12 years, 2 sons and 7. daughters, answered:

No one advised him, but people everywhere are talking about it!

Another question was asked as to what he actually knows about the so-called New

Island? Christian Schneider replied:

Nothing, except that it is undeveloped and could be built up with work.

Johannes Willig added:

The place is a better land, if one wants to work.

Philip Adam Hartmann responded to the same query:

By work one could earn in one yr. enough to live on for two years.

Georg Philip Mück answered:

The Queen of England will give bread to the people until they can produce

their own.

And Valentin Nomsboth aged 37, Reformed, came from the Braunfels area, married

12 years with 2 sons, said:

There is supposed to be a good land there, and, in a few years, one can get

both bread and land.

The prospective emigrant was then asked who told him such and under what

circumstances? Christian Schneider answered:

From a book from English agents with a carpenter from Essershausen, but he

hasn't read it. The carpenter quoted from it to him.

The emigrant was then asked a final question. From where does he think he will

get the means for this journey? Johannes Willig said:

He wants to sell what little he has.

Hanß Georg Gäberling noted:

He wants to sell his livestock.

Johann Philip Hetzel aged 36, Lutheran, married 16 years with 4 daughters and 2

sons, answered:

He wants to sell his few sheep.

Wentzel Dern aged 40, Lutheran, born in this country, married 14 years with

3 sons and 4 daughters, answered:

He wants to sell his cow, but leave his other possessions with friends.

Johann Wilhelm Klein aged 25, Lutheran, married since Christmas, gave an

important response:

The Queen will advance it to the people.

Johann Adam Fehd aged 30, Lutheran, born in this country, married With 1 son,

put his trust elsewhere:

He must have God's help!

But perhaps the most important yet most intangible factor in the emigration was

the character and psychological make-up of

the 1709ers themselves. They seemed to have within their souls Some special

spark, some sense of daring and adventure which enabled them to gamble their

lives and families on an unknown fate and set forth across a mighty ocean to a

strange land. Several emigrants were noted in churchbooks prior to 1709 as

"vagabondus" and thus were already on the move. Some exhibited a genuine

landhunger and a desire to better their lot even before leaving Germany, as

exemplified by a few of the responses to the Nassau-Weilburg questionaires.

And then there were those hearty souls who found their way to colonial N.Y.

who were simply dreamers, as shown by this rather caustic comment of the

Pastor of Welterod

[1709] In this year the winter was terrible cold and because of its fury the

spring crops of nut, cherry, and apple trees are almost gone...

A particularly deceptive spirit this year broke out among many people,

especially those more or less lazy and indolent fellows who left their

fatherland with wife and children to travel to England from where they

were to be transported to Carolina in the West Indies or America, about

which land they allowed themselves to dream again of great splendors where

one should almost believe that breakfast bread would rain into their mouths.

Moreover, they would not let themselves be deterred from their calm delusion

through more accurate respresentation of the facts. Out of my congregation

here, for example, a single, miserably lazy fellow babbled about this with

his wife and 3 children then left from here - namely Johann Curt Wüst from

Strüth. There were others there who came back again after repenting of

their foolishness, but he is not found among them.

I say, "Thank God for the dreamers!" One of the discoveries in my finding over

500 of the 847 New York Palatine families in their German homes is the fact that

so many emigrants originated in areas outside the boundaries of what we think of

today as the Palatinate. Many New York settlers were found in the Neuwied,

Isenburg, Westerwald, Darmstadt, and Nassau regions as well as the Pfalz -

proving again that the term "Palatine" was more of a generic reference (meaning

"Germans" in general) rather than a literal description of their precise,

geographic origins. The Pastor of Dreieichenhain midway between Darmstadt

and Frankfurt, substantiates the widespread origins or the 1709ers in an utterly

fascinating entry in his churchbook:

The year 1709 began with such severe and cold weather and lasted such a long

time that even the oldest people could not remember ever having experienced

such a winter; not only were many birds frozen and found dead, but also many

domesticated livestock in their sheds. Many trees froze, and the winter

grain was also very frozen...

In this year 1709 many thousands of families from Germany, especially from

Upper and Lower Hessen, from the Pfalz, Odenwald, Westerwald, and other

dominions, have departed for the so-called New America and, of course,

Carolina. Here, from out of the grove, (..) families have departed with them

[the families being those of Johann Henrich Michael Vatter, Friedrich Filippi,

Christoffel Schickedantz, Christoffel Jost, and Tobias Schilfer]. [Here are]

details of those who have joined together here and there in Germany and

departed in 1709 for the New World:

From the Pfalz 8,589 persons

From Darmstadt area 2,334

From Hanau, Ysenburg, and neighboring

Grafschaften and Wetterau districts 1,113

From Franckenland 653

From the Mainz area 63

From the Trier area 58

From the Bishopric of Worm, Speyer, and

neighboring Grafschaften 490

From the Kassel area 81

From the Zweibrücken area 125

From the Nassau area 203

From Alsace 413

From the Baden countryside 320

Unmarried craftsmen 871

(15,313)

Not all of these people went farther than to England and Ireland;

very few got to America. And because England and Ireland didn't

suit them, they all, except those who died on the way, returned,

as did some of the above mentioned Hanau families, and that after

two years. The Catholics, however, were all sent back.

Just how and where this village Pastor obtained these numbers and his information

intrigues me greatly, but no source is revealed in the Dreieichenhain churchbook.

However, the extract does indeed give a good, although undoubtedly incomplete,

picture of the overall geographic breakdown of the origins of the emigrants from

contemporary eyes.

The first trickle of German emigrants left for New York with Pastor Joshua

Kocherthal in 1708 and settled near Newburgh on the Hudson River. Then, about

February or March 1709, large groups began leaving their German homes for

Rotterdam and thence to England. There are records of their departure. Some

obtained letters of recommendation or birth certificates from officials to bring

with them on their trip, such as Gerhardt[\[1\]](NEEDLINK) Schäfer and

Ulrich[\[1\]](NEEDLINK) Simmendinger. Others tried to dispose of

their property in an orderly and legal manner and obtain lawful permits to

emigrate, such as

Peter[\[1\]](NEEDLINK) Wagener of Dachsenhausen and the many

1709ers who left the Nassau-Dillenburg region. As these Germans left their

homes, very often the local Pastors made mention of their departures in their

churchbooks. For instance, the registers at Bonfeld in the Kraichgau

have an entire page detailing the emigrants from the village (such as

Jost[\[1\]](NEEDLINK) Hite, Simeon[\[1\]](NEEDLINK)

Vogt, end Hans Micheel[\[1\]](NEEDLINK) Wagele) in 1710 as well as

latsr years. The Pastor at Weisloch noted that

Conrad[\[1\]](NEEDLINK) Dieffenbach emigrated with the family of

Georg Bleichardt[\[1\]](NEEDLINK) Hauck to the West Indies 15 May

1709, the minister at Leonbronn mentioned that Margaretha,

Lorentz[\[1\]](NEEDLINK), and Georg[\[1\]](NEEDLINK)

Däther went to England, and the Treschklingen register augmented the

Bonfeld churchbook by stating that Hans Jost Held

(Jast[\[1\]](NEEDLINK) Hite) emigrated with wife and child with

other people to Pennsylvania in the so-called new world in 1709. Sometimes

such a churchbook entry was quite a story filled with intrigue, as at Massenheim

Let it be known that this Spring many people left the country for English

America, namely the Island of Carolina, including also from here Matthaeus

Koch and his wife Christina together with their 4 children who went thither

and with them his mother Johann Henrich Aul's wife, between 60 and 70 years

of age. [Frau Aul, the mother of Matthaeus Koch,] went secretly in the night,

forsaking husband and children here and going to England, withoUt doubt to

find her grave in the ocean. On 27 Nov 1710, Johann Henrich Aul, a master

cooper whose wife left him and went with her two sons of a 1st marriage to

English America, married to Anna Margaretha Freund; Herr Aul was freed

[from his first wife] as she had been cited by the government in three

principalities and has not appeared.

The trip down the Rhine to Holland took anywhere from four to six weeks. A

personal account of an emigrant's journey from Alsheim to London in 1709, from

the Stauffer notebooks kindly sent to me by Klaus Wust, describes in detail what

probably was a typical route:

In the year 1709, I, Hans Stauffer, removed on the 5th of Nov with wife and

children Jacob, 13 yrs., Daniel 12 yrs., Henry, 9 yrs., Elizabeth with her

husband Paulus Friedt and one child, Maria by name, and myself, eight, we

set sail from Weissenau on the 8 day of Nov. At Bingen we remained one day,

and we left on the 10th day of Nov. at Hebstet, we set sail on the 11th day

of Nov. Neuwied, we set sail on the 12th day of Nov. At Erbsen, we set sail

on the 13th day of Nov and came to Millem. There we had to remain one day.

On the 15th day, we left Millem. At Eisen we lay two days. On Nov 17th we

sailed away [to Erding].

And on the 20th day of Nov, we left Erding and sailed half an hour under

Wiesol. And on the 21st we went to the shore. There we had to remain until

the wind became calm. And on the 22nd of Nov, we sailed as far as Emrig.

There we had to remain until the wind became calm. And on the 24th of Nov,

we left Emrig and

came to Schingen Schantzs, and [CUTOFF]

the night [we sailed] to Rein and on the 28th of Nov to Wieg, and thence we

came to Ghert on the 29th of Nov. On the first day of Dec, we came to

Amsterdam. And on the 17th of Dec we left Amsterdam and sailed half an hour

before the city. There we had to remain until the wind became favorable and

calm. And on the 19th day of Dec, we came to Rotterdam. There we had to

wait until the tide was ready for sailing. Thirteen days we had to remain.

On the 29th of Dec we sailed from Rotterdam nearly to Brielle. There we had

to remain until the wind was favorable. On the 20th day of Jan we left

Brielle and sailed to London. We sailed six days on the sea to London.

As the Germans assembled in Holland awaiting transportation to England, ever so

often they participated in a baptism performed by a Dutch Pastor of their host

country. For example, at the christening of a child of Jeremias Schletzer

sponsored by eventual New York settlers Benedict[\[1\]](NEEDLINK)

Wennerich and Maria Elisabetha[\[2\]](NEEDLINK) Lucas in April of 1709,

the Pastor of the Rotterdam Lutheran Church noted that the party was from the

Palatinate, professing to go to Pennsylvania; and at the baptism of a child of

Dirck Luijckasz (Dieterich[\[1\]](NEEDLINK) Laux?) in September 1709,

the Pastor of Rotterdam Reformed Church recorded that the parents were outside

the Eastgate, coming from the Pfalz, and going to England. Similar entries

concerning these German emigrants are found in the Rotterdam Catholic registers

and the Brielle Reformed churchbooks.

The Palatines encamped outside Rotterdam were in a miserable condition, and

shacks covered with reeds were the only shelter they had from the elements.

The Burgomaster of Rotterdam took pity on them and appropriated 750 guilders for

distribution among the destitute. Meanwhile, the British government employed

three Anabaptist Dutch merchants, Hendrik van Toren, Jan van Gent, and John

Suderman, to supervise the loading and sailing of the emigrants to England (the

five Rotterdam Embarkation Lists are a product of their labours); but the

Palatines continued to arrive in Holland in increasing numbers at the rate of

nearly a thousand per week. On 14 June 1709, James Dayrolle, British Resident

at the Hague, informed London that if the British government continued to give

bounty to the Palatines and encourage their migration, half of Germany would be

on their doorstep, for they were flying away not only from the Palatinate, but

from all other countries in the neighborhood of the Rhine!

Things were clearly getting out of hand. The immigrants were coming over so fast

that it was impossible to care for them and dispose of them. The British,

victims of their own too-successful PR campaign, tried to turn back many Palatines,

especially the Catholics, and by late July refused to honor their

commitments to support the German arrivals. Many of those arriving after that

date, if not sent back, made their way to England by private charitable

contribution or at their own expense; this latter group probably never was

catalogued or enrolled on any shipping list as were the earlier arrivals at

Rotterdam.

The Palatines arriving in England beginning In may 1709 continued to have

problems there. London was not so large a city that 11,000 alien people could

be poured into it conveniently without good notice or thorough planning. The

government attempted to cope with the trying situation but it was hard put to

provide food and shelter for the emigrants. 1,600 tents were issued by the

government for the Palatine encampments formed at Blackheath, Greenwich, and

Cumberwell; others were quartered at Deptford, Walworth, Kensington, Tower Ditch,

and other areas. Pastor Fred Weiser has sent on a genealogical source

indicating the Palatine's travail in London: some interesting marginal notes

found in the family record of the 1709er Arnold Altlander/Altlanden family of

Plänig near Alzey mention that one of the children born in 1706 "fell blessedly

asleep in the Lord Christ and was buried at Derthforth near London," while another

child born in 1708 "was buried in London on the heath." Palatine deaths in

England were not uncommon as their places of shelter were as crowded and

unhealthy as they had been in Holland. Occasionally an emigrant's marriage or

baptism was recorded in a British source, such as the Savoy German Lutheran

churchbook in London; this material has been transcribed and published by John P.

Dern in his valuable London Churchbooks and The German Emigration of 1709.

Mr. Dern and his late colleague Norman C. Wittwer also found several Palatine

baptisms (including one in Johann Peter[\[2\]](NEEDLINK) Zenger's

family) registered at St. Nicholas Church in Deptford.

While the emigrants waited in England, the Board of Trade ordered two German

Pastors, Pfr. John Tribbeko and Pfr. Georg Andrew Ruparti, to compile a record

of those encamped in London. Their rolls are known today as the four London

Lists, but they cease in June 1709 when the Palatine emigration simply got too

big to chronicle. The longer they lingered, the worse conditions became for the

1709ers; so, as in Rotterdam, they had to depend on alms and charity to survive

in their camps at Blackheath and environs. At first the London populace looked

on the Palatines in a rather kindly way, but gradually the novelty of their

presence wore off. As the poorer classes of Londoners realized the emigrants

were taking their bread and reducing their scale of wages, mobs of people began

attacking the Palatines with axes, hammers, and scythes, and even the upper

classes became alienated

from the Germans, fearing they were spreading fever and disease. To alleviate

the situation, groups of Palatines (labelled "Catholics," although some

definitely were not) were sent back to Holland from whence they were to return

to Germany. Dr. Knittle has published two such "Returned to Holland Lists"

dated 1709 and 1711. Working from a clue found in the Groves Papers at the

Public Record Office in Belfast, I employed Peter Wilson Coldham to search for

similar lists dated 1710, which eventually were found in the Treasury Papers

in the London Public Record Office and published by John P. Dern and myself in

1981 in Pfälzer-Palatines as a tribute to the late Dr. Fritz Braun of the

Heimatstelle Pfalz.

The dispersal of the Palatines continued. Some were sent to other parts of

England where, rather than receiving their expected grants of land, they were

made daylaborers and swineherds. Others were dispatched to Ireland, where

many became tenants of Sir Thomas Southwell near Rathkeale in County Limerick

(my small book The Palatine Families of Ireland concerns these 1709ers and

their descendants. Then, some emigrants were sent to North Carolina where

they joined the Swiss settlement of Christopher von Graffenreid, while a few

others went to Jamaica and the West Indies. Plans also were instituted to

transport a group of Germans to the Scilly Isles, but this scheme appears to

have come to naught.

Of the 13,000 Germans who reached London in 1709, only an estimated quarter

came to New York. The idea of sending the Palatines there sprang from a

proposal sponsored by Governor-Elect Robert Hunter of New York, probably made

originally by the Earl of Sunderland. It was their thought that the 1709ers

be used in the manufacture of naval stores (e.g. tar and pitch) from the pine

trees dotting the Hudson Valley and thus earn their keep in the colony.

It also was acknowledged that a strong Palatine presense in the new world would

act as a buffer against the French in Canada and strengthen the Protestant cause

in British America. No real time-limit to the lehgth of service of the Germans

was specified, but it was apparent they were to be employed until the profits

had not only paid their expenses, but also repaid the government for their

transportation and settlement. They allegedly signed a covenant to this effect

in England which noted that, when the government was repaid, forty acres of land

would be given to each person, free from taxes and quit rents for seven years.

Most of the Palentines boarded ships for New York in December 1709, but the

convoy really never left England Until April of 2010. The German Emigrants

sailed on eleven boats, and Governor-Elect Hunter accompanied the group. The

voyage was a terrible

one for the Palatines: they were crowded together on the small vessels,

suffered from vermin and poor sanitat!on, and were forced to subsist on

unhealthy food. Many became ill, and the entire fleet was ravaged by

ship-fever (now known an typhus) which eventually caused the deaths of many

passengers. John P. Dorn will publish the results of his research with Norman

C. Wittwer on the the Palentines' journey to America, the convoy that

accompanied them, their route of travel, etc., which will greatly enhance our

knowledge of that little-known aspect of the 17O9er story.

The Palatines who arrived in the summer of 1710 found that colonial Now York was

hardly the paradise propounded In the Golden Book back in Germany. The New York

City Council protested the arrival of 2,500 disease-laden newcomers within their

jurisdiction and demanded the Germans stay in tents on Nutten (Governor's) Island

offshore. Typhus continued to decimate the emigrants. Altogether about 470

Palatines died on the voyage from England and during their first month in New York.

Many families were broken up at this time; Hunter apprenticed children who were

orphans as well as youngsters whose parents were still alive! The Governor's

record of his payments for the subsistence of the 847 Palatine families 1710-1712

survives today as the so-called Hunter Susistence Lists.

On 29 September 1710, Governor Hunter entered into an agreement with Robert

Livingston, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, to purchase a tract of 6,000 acres

on the east side of the Hudson for the purpose of settling Palatines there to

manufacture naval stores. In October, many of the Germans began going up the

river, clearing the ground, and building huts on the Livingston tract.

Gradually, small, distinct settlements appeared at East Camp called Hunterstown,

Queensbury, Annsbury, and Haysbury; the villages on the west side of the Hudson

were Elizabeth Town, George Town, and New Town. Other 1709ers remained in New

York City, and many of this group eventually made their way to New Jersey.

The Palatines grew increasingly dissatisfied with their status, which bordered on

serfdom, and strongly demanded the lands promised them in London. Their

rebellion was put down by the governor, who disarmed the Germans and put them

under the command of overseers and a Court of Palatine Commissioners, who treated

them again as "the Queen's hired servants." Dissension continued, as the

Palatines bickered with their commissaries and found fault with the irregular

manner in which they were being subsisted with inferior food supplies.

The situation grew worse due to trouble in the naval stores program: the

knowledgeable James Bridger was replaced with Richard Sackett who seemed to

know little about tar-making. In

1711, many Palatines took part in an abortive British expedition against the

French in Canada, further delaying tar extraction.

To add to this sad state of affairs, in England the Whigs, who had largely

sponsored the Paletine settlement in New York, were superseded in office by the

Tories, who proceeded to disparage the 1709er Whig project and bring about a

House of Commons investigation and censure in 1711. Hunter then lost financial

backing in his efforts to support the Germans and had to withdraw the Palatine

subsistenses in September 1712. After all the British promises, the Germans

were abandoned to suffer their own fate, although the Governor still attempted

to keep some control over them by requiring the Palatines to obtain permits if

they wished to move elsewhere in New York or New Jersey. Johann Friederich[\[1\]](NEEDLINK) Hager,

the Reformed German clergyman sent to minister to the Palatines by the Society

for the Propagation Of The Gospel in London, described their terrible plight in a

poignant letter dated 6 July 1713 written to the Society:

Pray to not take it ill that I trouble you with these lines. I have written

several times, but I do not know whether the letters have come to hand. Thus

have I likewise received none from my father, I do not know how long since,

and therefore, cannot be sure whether he is alive or dead.

The misery of these poor Palatines I every day behold has thrown me into such

a fit of melancholy that I much fear a sickness. There has been a great famine

among them this winter, and does hold on still, in so much that they boil

grass and ye ch. eat the leaves of the trees. Such amongst them have most

suffered of hunger as are advanced In yrs. and too weak to go out labouring.

I have teen old men and women crie that it should have almost moved a stone.

I am almost resined with this people. I have given the bread out of my own

mouth to many a one of them, not being able to behold their extreme want.

Where I live there were two old people that, before I could be informed of

their necessitous condition, have for a whole week together had nothing but

Welsh turnips, which they did only scrape and eat without any salt or fat or

bread; and in a word, I cannot describe the miserable state they are reduced

to, and above all that, have we no hope of any alteration; for one hears no

news here, nobody receives any letters, which also hinders me now from

drawing a Bill of Exchange for my half year'a salary, due Ladyday 1713. The

knife is almost put to my throat, whilst I am in a foreign country without

either money or friends to advance one any. I had sown and planted some

ground at my own charges, but it has now twice been spoiled. I have served

hitherto faithfully as Col. Heathcote and others can bear witness with a good

conscience and should I now be forsaken in this remote land without any pay,

or means of subsistence, having neither received anything hitherto from my

people nor anything being to be expected from them for the time to come.

They cry out after me: I should by no means forsake them for they should

otherwise be

quite comfortless in this wilderness. Sir, I entreat you to recommend my

case as much as possible, for I do not know where to turn myself otherwise...

Having been left to their own resources, the more restless and adventurous of the

Germans stole away in late 1712 to the Schoharie valley, which at one time was a

land considered for Palatine settlement. They bought lands from the Indians there,

but also bought more trouble as the Native-Americans' title to this property was

dubious and led to years of litigation. Slowly, the Palatines carved homes out

of the frontier, and eventually seven distinct villages were settled in the

Sohoherie region. Frank E. Lichtenthaeler, in his excellent article The Seven

Dorfs Of Schoharie has identified them as:

Named by Conrad Weiser's Journal Named by Simmendinger -------------------------------- --------------------- 1) Kniskern-dorf Neu-Heidelberg 2) Gerlachs-dorf Neu-Cassel 3) Fuchsen-dorf Neu-Heessberg 4) Schmidts-dorf Neu-Quunsberg 5) Weisers-dorf (Brunnendorf) Neu-Stuttgardt 6) Hartmans-dorf Neu-Ansberg 7) Ober Weisers-dorfPalatines had not been permitted to bring their Hudson Valley tools with them to Schoharie, so they fashioned ingenious substitutes: branches of a tree for a fork used in haymaking, a shovel from a hollowed-out log-end, and a maul from a large knot of wood -- examples of their determination and imagination. By the time of their naturalization in 1715, the 1709ers were spread out in colonial New York to a large extent. About this time, Ulrich[\[1\]](NEEDLINK) Simmendinger began gathering family data concerning his compatriots which he would eventually publish in 1717 upon his return to Germany (see his section for further details). Simmendinger's fascinating pamphlet detailed the families at East Camp, those at Rhinebeck and on the west side of the Hudson (lumped together in his "Beckmansland" locale), the Germans in the Schoharie settlements, those in New York City, and groups in New Jersey at Hackensack and on the Raritan. These latter New Jersey Germans (whom Dr. Knittle erroneously put as Schoharie residents of Kniskernsdorf) settled in the colony after subsistence was withdrawn in 1712. N.J. Lutheran congregations in fairly close association were formed at Millstone, Rockaway, and an area known as "The Mountains." Excellent data on them may be found in John F. Dern's Albany Protocol, Simon Hart and Harry J. Kreider's Lutheran Church in N.Y. and N.J. 1722 - 1760, and Norman C. Wittwer's The Faithful and the Bold. Troubles with the New York colonial government continued as Hunter made plans to clear the Palatines from their Schoharie

settlements. In 1718, Johann Conrad[\[1\]](NEEDLINK)

Weiser, Gerhardt[\[1\]](NEEDLINK)' Walrath, and Wilhelm[\[1\]](NEEDLINK)

Scheff were sent to London to plead the Palatine cause; however, the lack of

agreement among the three delegates, their lack of financial resources, and

Hunter's powerful influence in London made their case ineffective, and they

returned to New York. Finally, in 1722/23, Hunter's successor, Governor William

Burnet, purchased land in the Mohawk Valley far some of the Palatines, and they

eventually settled in this area on the Stone Arabia and Burnetsfield Patents.

About this time, fifteen German families left the Schoharie Valley to settle in

the Tulpehocken region of present-day Berks County, Pennsylvania. Others

continued to follow, and by 1730 the 1709er emigrant families were found in

New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvaaia, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, Connecticut,

and the Carolinas.

This, then, is a necessarily brief background of the Palatine story. I especially

recommend Dr. Walter A. Knittle's book Early Eighteenth Century Palatine Emigration,

which has helped me greatly, for a fuller picture of their travails and dispersal.

That the Palatines survived in America is no less a miracle than is their emigration!

They left hardships in Germany to find new hardships here. The 1709ers never

found the promised land of milk and honey of the Golden Book, but they did find a

wilderness ready to be tamed and transformed into liveable communities by

perseverance and hard work. Their story is a tribute to their fortitude and

quality of character which enabled the to find the inner strength to meet the

terrible difficulties they faced in their new life in a new world. The Palatine

families of New York met the challenge headon and not only survived, but established

a secure and important place in American life.

The Palatines Arrive in the Hudson River Valley 1710

Becker, John Adams; Families, Ontario Genealogical Society, Nov. 2009

Genealogy Pages

- Genealogy Overview

- The Babcock Line

- Mirror of the now inactive CrandallGenealogy.com

- The Dombrowski Line

- The Parker Line

- The Winters Line

- History of the Palatines

- Sources & Notes